All The Light We Could Not See

What the fascinating discovery of a bakery in Pompeii reveals about us

This summer, there was a big buzz in the Italian news when a fresco of what looks like a pizza emerged from the ongoing excavations at Pompeii. Nearby Naples is the birthplace of pizza and a city where pizzaioli (pizza makers) are celebrities so the possibility that pizza’s ancient ancestor had been discovered was thrilling.

Last week's news revealed a bakery on the other side of the frescoed wall. Inside is a small room with grist mills and only one window covered by iron bars. It provided little light because it faced the house's interior, where the bakery owners presumably lived. Enslaved people would have been confined day and night to this almost airless room along with donkeys. Archaeologists can determine by the grooves around the mills that the people and animals would have spent their days encircling the small area around the mills to grind the grain. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, Director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, emphasized in his press release that this discovery of a “bakery-prison” is a grim look at what slavery was really like in the ancient, fabled city.

The appalling conditions under which enslaved people toiled in bakeries were documented by the second-century writer Apuleius, and there are dozens of bakeries already excavated at Pompeii, but in past eras, this wouldn’t have been a newsworthy discovery. An ancient bakery, easily recognizable because it looks much like one functioning today, would have been too small and ordinary to be interesting, so early excavators would have plowed right through the walls without considering the entire physical space. The most unusual thing about this bakery is our willingness to look at the complete picture instead of the usual cropping of history.

A Treasure Hunt

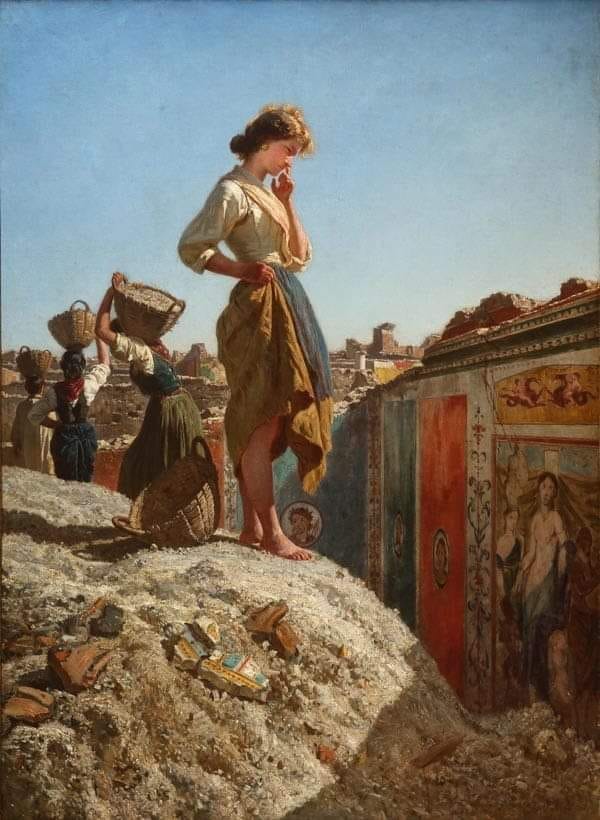

Pompeii was first excavated in 1748 under the auspices of the Bourbon Kings. Archaeology didn’t even exist, and the first explorations would have been thrilling treasure hunts. Extraordinary bronze statues were pulled from Herculaneum, as were elaborate mosaics and marble sculptures. Painted walls emerged whole and in pieces and would have been 100 times brighter than they are today after having been kept dark and airtight for centuries. As the lost city’s stuff was unearthed, much of it was looted and sold. The best was moved to a military barracks in Naples, which eventually became the archaeological museum. Wealthy Grand Tourists saw Pompeii as the world’s greatest open-air market, and they purchased antiquities, which are now scattered throughout museums and private collections worldwide.

The churches and palaces built during the 18th century in Naples are full of marble recycled from Pompeii. There is only one small marble quarry in Southern Italy, but the Romans had marble from all corners of the Empire, which the Bourbon monarchy deployed to beautify Naples during its most spectacular period. The fertile soil of Mount Vesuvius bore not only the best fruit and vegetables but also the most exquisite artwork and materials, which lay waiting in the ground like a gift from their ancestors.

The Bodies Emerge

Excavations continued slowly and methodically through the 1860s. The world order was changed by the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Neapolitan Revolution. Monarchies were diminished, and modern democracy was born. In 1863, Giuseppe Fiorelli, the man in charge of Pompeii, perfected his technique of pouring the plaster of Paris into the hollow spaces he detected inside the volcanic material. What emerged for the first time were the people who died at Pompeii.

The agony of their final moments was exhibited right next to the ruins and made Pompeii the most famous archaeological site in the world. Fiorelli wrote about them, and the plaster casts became almost characters, which toured the world with names like “The Lovers”. Only with recent scientific instruments do we know that the casts were sometimes augmented to heighten their emotional impact. The cast of the man who rests his hands on his head as he accepts his fate was actually armless — his arms were added by the 19th-century cast makers.

A Moral Dilemma

During the Victorian era, British archaeologists made discoveries in Pompeii that led to a lot of moralizing about the sin and vice that led to the fall of the Roman Empire. The British Empire was at its zenith, so many people were anxiously attuned to the lessons buried at Pompeii.

That era’s obsession with the occult shows itself in interpreting the frescoes discovered inside what they called the Villa of the Mysteries. An elaborate interpretation of the frescoes as scenes from a cult initiation has more to do with Alastair Crowley than Pliny. This theory relies on the frescoes having been painted for a secret room in the house where the cult would have gathered. Visit today, and you will see the room is obviously a dining room, not at all hidden, with windows that overlook the Bay of Naples.

Pompeii was badly damaged in World War II and also had to contend with weather, mudslides, other eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, and mass tourism. In the early 2000s, much of what had been excavated was in peril. Silvio Berlusconi’s appointees siphoned money from the site with inflated construction contracts and mafia labor until the “School of the Gladiators” implosion brought worldwide attention and disgrace to Pompeii.

Stopping the tomb raiders

The era of Massimo Osanna as Director is a comeback story. With little money and a tiny staff, he began doing night tours and wine tastings to energize visitors. With an influx of money from the European Union, Osanna dedicated energy toward restoring the gladiator school and the Villa of the Mysteries. He initiated an era he called “global archaeology,” where he invited experts from all disciplines to work and study Pompeii, including computer scientists, dentists, geneticists, paleobotanists, plumbers, and winemakers.

There was also the problem of Regio V, a mostly unexcavated corner of the city, which historians know was a wealthy district. Tombaroli or “tomb raiders” also know this and had been tunneling into the site from adjacent farms. Though there was already more than enough known material to contend with, the Great Pompeii Project was initiated partly to stop the tombaroli.

How the other half lived

When Zuchtriegel took over Osanna’s position in 2021, he made clear that his era of leadership would be marked by looking at what life was like for Pompeii's poorest, least powerful people. It’s now estimated that at least 20,000 people lived in Pompeii, and half of them may have been enslaved. Because so much is known about the wealthiest citizens, special attention will now be paid to those whose stories have not yet been told.

With the breadth of scholarship to draw on and world-class technological instruments, the past has been brought to life at Pompeii in ways that were previously unimaginable. Now, we must also look at what we don’t want to imagine because the past lights the way to the future, and the chance to do it better is always ours.

Love that last paragraph that so beautifully addresses the contradiction at the heart of Ancient Rome-- the awe-inspiring beauty and the brutality underneath it all. Worth pondering these days as well. Wonderful post!